There was an irresistible TV mini-series on VH1 called “I love the 1980s" that debuted late in 2002. Over the course of ten episodes, VH1 showcased each year of the 80s and all the stuff that defined that year: popular music, fashion, trends, TV shows, movies, and occasionally something about politics. The show was so successful that it moved to MTV, and they created a mini series for "I Love the 60s", "I Love the 70s", and "I Love the 90s." Everyone was getting nostalgic and it was awesome.

One of the trademarks of the show was celebrities talking about why and how trends caught on during each decade. We’ve heard these stories before:

- In the 1960s, The Beatles had shaggy hair, and then no young person on the planet got a haircut for a decade.

- In the 1970s, polyester was introduced to fashion, and cotton wasn’t seen again for years.

- In the 1980s, Run DMC kicked off a suburban rap music revolution.

- In the 1990s, Saved by the Bell made everyone want acid washed jeans.

However rewarding it is to hear these stories on the shows, they were rife with what psychologists call hindsight bias:

Hindsight bias is the inclination, after an event has occurred, to see the event as having been predictable, despite there having been little or no objective basis for predicting it.

Another way to say it: it’s easy to make sense of things that have already happened.

Think of sports fans. If their football team wins, they can tell you a long list of reasons why their team won the game. But if the wind would have blown the football outside of the goalposts and their team lost by a point, they would have been forced to explain the many reasons why their team lost. It's the same game. The only thing that changed was a gust of wind. Yet they find evidence to support the outcome.

If you pick through the facts of any situation, you can draw almost any conclusion.

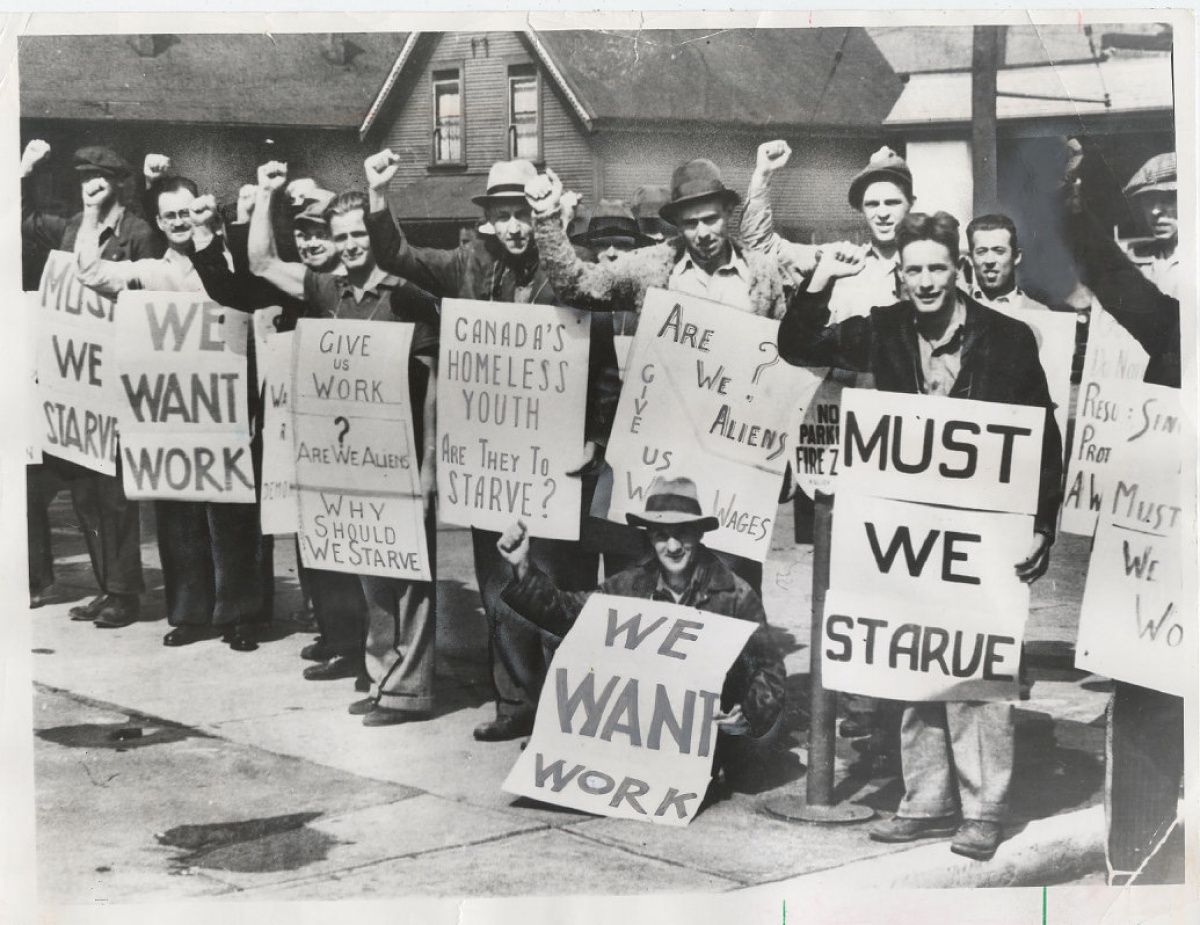

Hindsight Bias is Everywhere

Surprisingly, many business authors and bloggers fall victim to hindsight bias. These writers look back at winners and losers in the business world, and then they string together theories to explain why it happened. Their hope is that their storytelling will be so compelling that you'll agree with anything else they write. Ironically, I've found very few of these authors who have the courage to predict the future--this takes too much nerve. It leaves you vulnerable because you might be wrong.

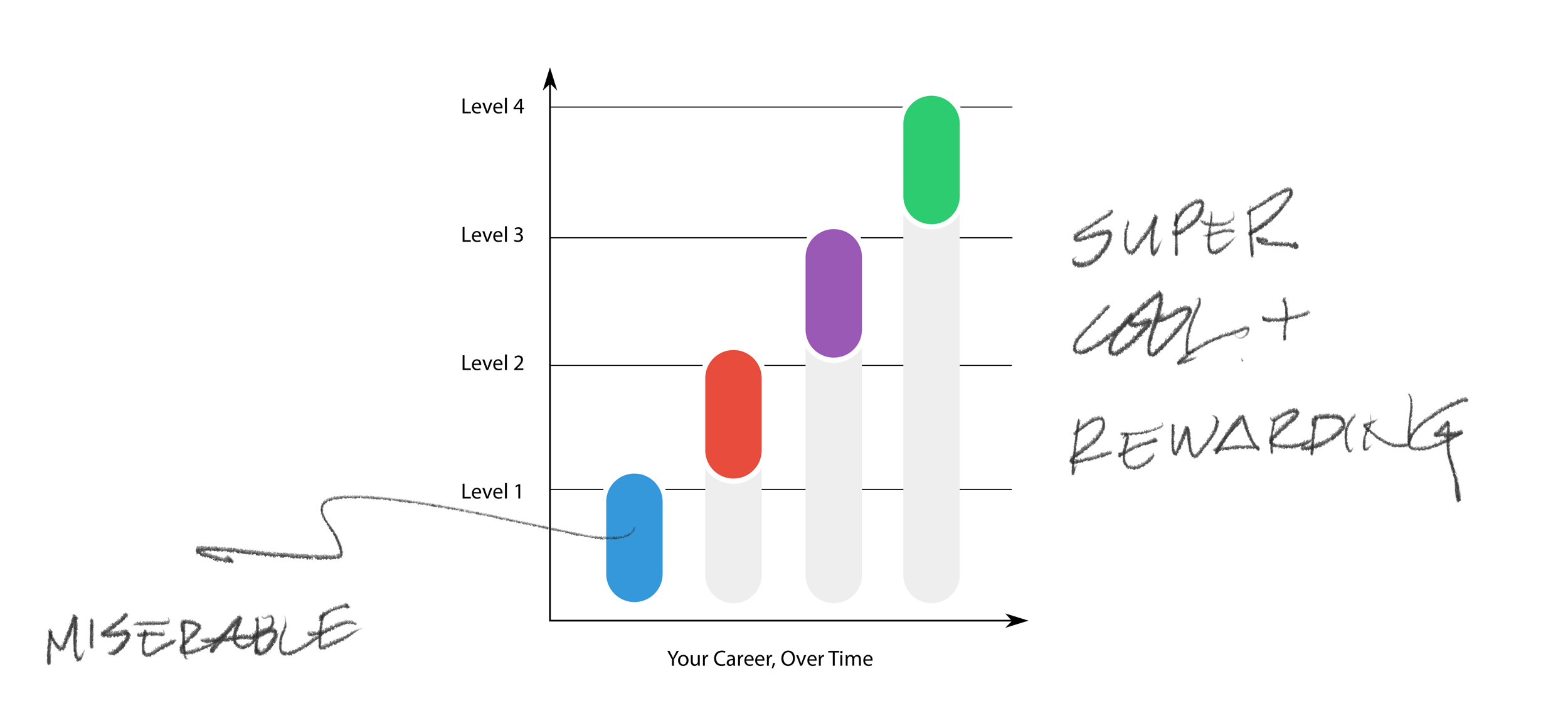

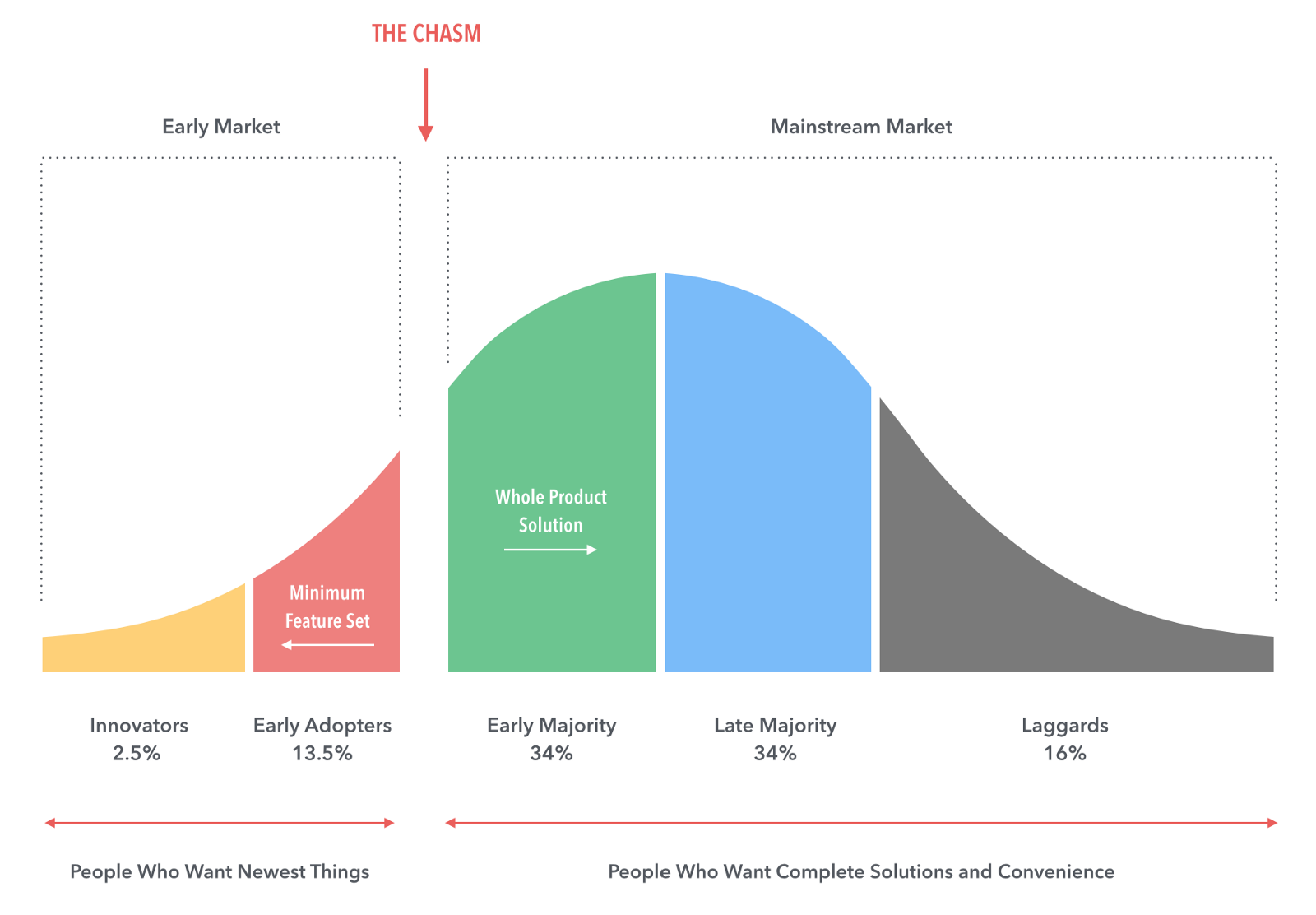

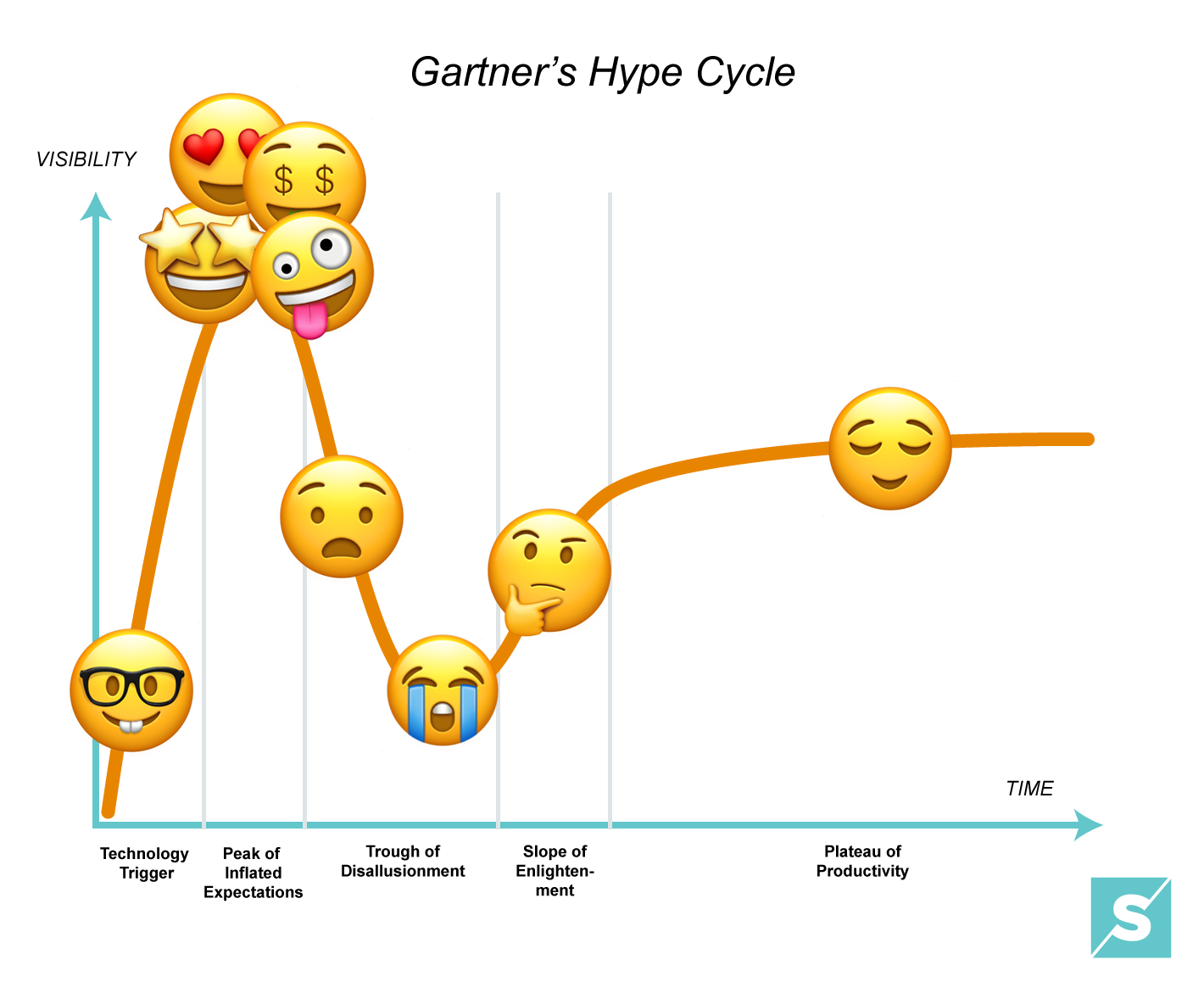

I guess that's why I geek out on Gartner's Hype Cycle and Crossing the Chasm. These are two models that are informed by the past, tested in the present, and then boldly suggest what will happen next.

Hindsight bias, somehow, seems to be woven deeply into the fabric of many professions. If you expose your financial track record to a financial planner, he'll tell you all the things that you did right and wrong. This has happened for decades.

Life coaches? It's a new profession, and I'm still not sure what they do or how this works. But it seems that the most popular life coaches on social media spend 50% of their time explaining what happened in the past, 25% of their time sharing a soft "key to life," and the remaining 25% of their time selling their service or book. Is it wrong that I would expect more courage from people who have declared themselves "life coaches"?

Where ever you are, be careful about hindsight bias. It’s natural to look back at what happened and to look for a logical explanation. It’s what we do at home, at work, and in our society. But resist telling those stories again and again. Because the longer you tell the story, the more clear it will become that your story was insufficient.